By: Ramzi Rihan

Taken from Birzeit University: The Story of a National Institution

Birzeit College phased out the secondary school level and became exclusively a junior college in 1967, the same year that Israel occupied the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Syrian Golan Heights. Palestinian society once again had to cope with the effects of massive displacement together with foreign military occupation. Civil protest was harshly dealt with; mass arrests were common, and Israel frequently deported Palestinians with leadership potential to Jordan and Lebanon.

Birzeit College administrators quickly concluded that the agreements they had reached with the American University of Beirut and other universities to accept Birzeit students as transfer students would not be sufficient to address the new realities created by the occupation. The number of students accepted by regional universities was limited, the cost was prohibitive (especially in times of economic downturn), and travel restrictions placed by the Israeli military authorities prohibited many students from venturing from the Occupied Palestinian Territory for fear they might not be allowed to return, nor was the regional political situation stable in the early 1970s. Clearly, there was a need for a local four-year university.

Interest in providing local higher education opportunities was shared by many people—educators, mayors, and community figures—in the aftermath of the 1967 war as it became clear that the occupation was turning into a long phase in Palestinian history rather than a brief interlude. A small Sharia (Islamic law) college was established in Hebron in 1971 and became the nucleus of Hebron University in 1980. A Catholic school in Bethlehem became the campus of Bethlehem University in 1973. The beginning of the transformation of Birzeit College into Birzeit University in 1972 was an important landmark within this process.

The initial thinking and planning to transform Birzeit College into a university stemmed from discussions that Hanna Nasir, Gabi Baramki, and I had in our capacity as senior administrators. At the 1972 ceremony to award associate degrees, Hanna announced that students who entered Birzeit College the following September could plan to graduate from it four years later with bachelor’s degrees. It was a bold announcement considering that the plans for that transformation were still preliminary; it signaled that Palestinians would take action as they see fit.

At the time, little did we imagine that our decision would have such far-reaching consequences. What seemed to be a natural but modest development turned out to be the first step in the creation of a large and diverse Palestinian higher education system that is considered by many to be one of the major lasting achievements of Palestinians under occupation.

Weeks after that initial announcement at the commencement ceremony, we placed notices in local newspapers announcing our plans and inviting students to apply. Predictably, the Israeli occupation authorities, represented by someone known to everyone as Captain Maurice, phoned to object, and I happened to be the only administrator available to take the call; I said that the notice would not be run again. (In fact, the initial notice had generated a flood of applicants, a clear sign that the decision addressed a real social need and gave an opportunity to those who could not afford to leave the Occupied Palestinian Territory to get a university education.) It is sobering to realize that had an Israeli bureaucrat not been reassured by an ambiguous response to his order or had he taken more decisive steps to stop us before our plans took shape, the fate of Birzeit University as well as all the universities that emerged in its wake would have been very different.

First Steps

Looking back, our plans were fairly modest: We anticipated enrollment of 600 students (up from around 200), and we would offer a basic liberal arts curriculum. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that our eagerness and commitment blinded us to some of the very real obstacles in our path. We did not know SWOT analysis, log frame (did these buzz words even exist then?), or any of the other jargon that has come to dominate professional management and planning, but we were determined to forge ahead, and we learned as we went along.

To facilitate the institution’s transformation into a four-year university, the Nasir family decided to convert the legal structure of the College from a private, family-owned institution to a public one and to entrust its supervision to a nonprofit foundation. The informal group that had overseen the College until then (consisting of Nasir family members and some of their friends) was replaced by an official Board of Trustees that was more representative of the Palestinian community. (The Board was formed in 1973 but was not registered by the Israeli occupation authorities until 1978.) The Board enacted its internal regulations and approved the statutes of the University and subsequent by-laws and regulations organizing all the operations of the University. This institutionalization process went on for a few years in the mid1970s. Samia Khoury, a founding member of the Board, led this process, together with the participation of the administration and other members of the Board.

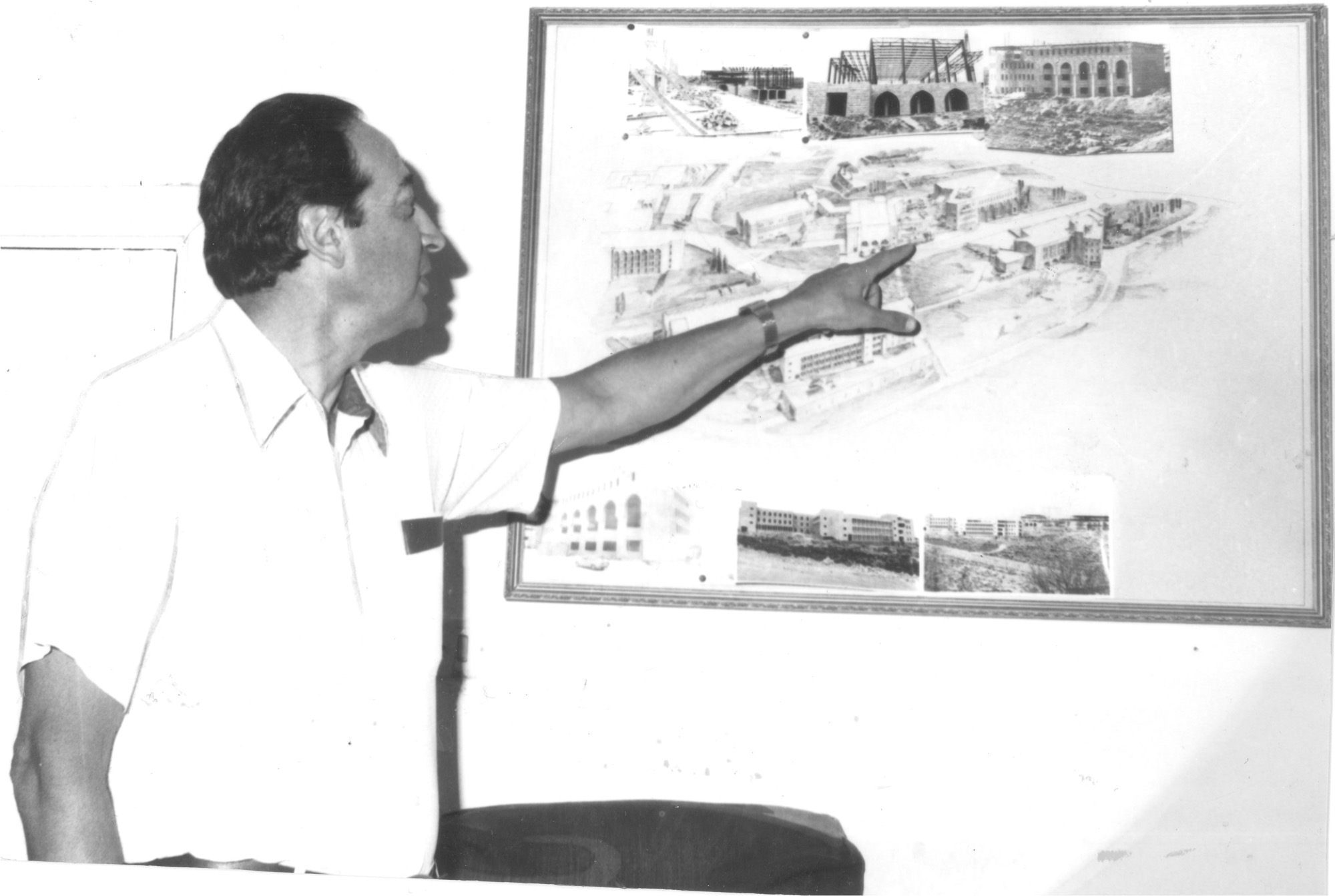

With the plans to develop the College into a university came the realization that the existing campus could not possibly accommodate the anticipated growth. Architectural plans were begun for a new campus intended to accommodate the future growth of the institution, originally planned for Tireh, a suburb of Ramallah. The Israeli authorities refused to license the project and the location of the new campus was moved to Birzeit. Initially, the Nasir family donated land it owned on the southern outskirts of Birzeit to the Board of Trustees, and in later years the Board purchased land as well for the purpose of building a new campus that could handle the anticipated growth in the number of students and of academic programs. The new campus was inaugurated in 1980 and quickly grew far beyond the original plans.

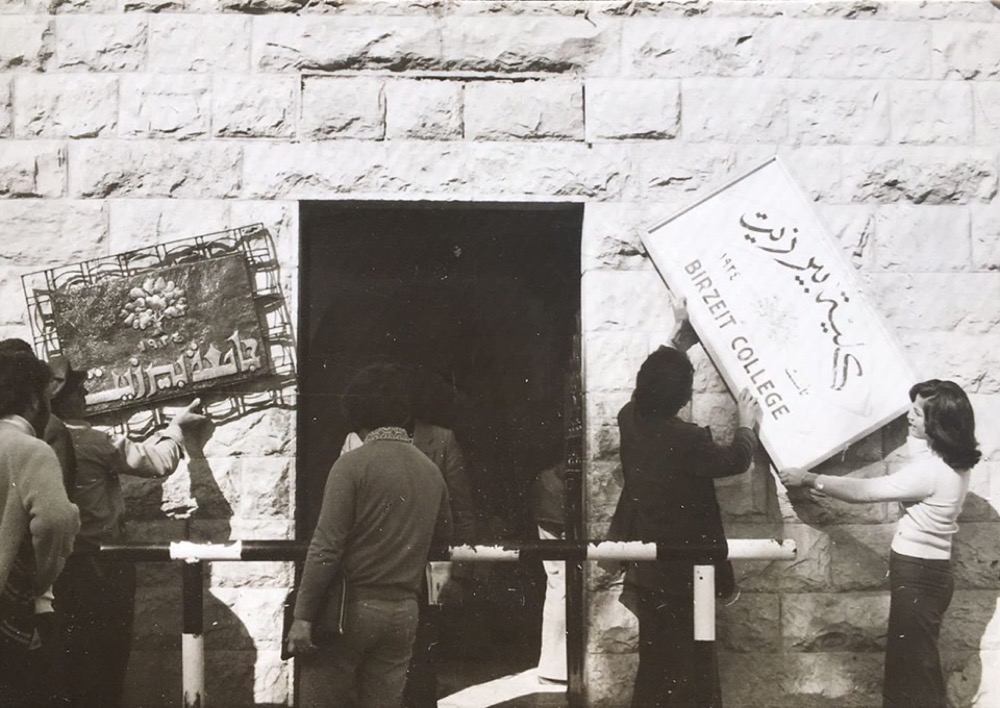

Transition

The academic year 1974-75 marked the true turning point. Academic departments were established as third-year (junior) courses were offered for the first time. This was the real transformation from a college to a university, although the name Birzeit University was not adopted until 1975-76. Some students who had previously completed the two years needed for the associate degree returned to continue their studies for a bachelor’s degree. The enthusiasm and involvement of the faculty was an invaluable asset in this transition. Faculty members from abroad joined the institution; many of them stayed only one or two years. In the meantime, as the student body grew, existing facilities became insufficient. So every summer, old space was renovated to accommodate the growth, and some space had to be rented.

As the University grew, human resource needs were as important as financial resources. The American organization AMIDEAST initiated an ambitious faculty development program in the late 1970s to support graduate studies for qualified candidates who would then return to teach in the institutions that sponsored them. Birzeit and other Palestinian institutions of higher education benefited significantly from this program.

In April 1976, Birzeit became the first Palestinian institution to be admitted to the Association of Arab Universities; three months later, the University granted its first bachelor’s degrees. In 1977, Birzeit became a member of the International Association of Universities.

The transition from college to university took place while the institution was still reeling from the Israeli occupation authority’s illegal deportation of University President Hanna Nasir on November 21, 1974. The deportation of the president at this sensitive juncture in the development of the institution was a severe and sudden blow, but we did not allow it to derail us. Gabi Baramki took over immediately as vice-president (in effect, as Acting President), Hanna embarked on public relations and fundraising activities in many countries, and I led much of the planning effort that was required during the transitional period. For two decades, Gabi ran the University and bore the brunt of handling, with perseverance and patience, the many normal and abnormal problems, maintaining constant communication with Hanna’s office in Amman.

Student Body

Council for Higher Education

In June 1977 the Union of Professional Associations (the umbrella organization for doctors, engineers, and other professionals) sponsored a conference on Palestinian higher education in Jerusalem. Representing Birzeit University, I proposed the establishment of a multicampus central Palestine University; each campus could offer an area of expertise.

This proposal (which had been proposed earlier by Birzeit College in 1971 and rejected) was rejected once again because other institutions preferred to act independently. This decision has had some unfortunate consequences for all universities, including Birzeit—the unchecked growth of programs rather than planned development to meet the social and economic needs of the population base, competition rather than cooperation among institutions, and duplication of programs rather than diversity. The Union was headed by Ibrahim Daqqaq, who later became chairman of the Board of Trustees of Birzeit University. The conference resulted in the creation of the Palestinian Council for Higher Education. In the absence of a Palestinian government, the Council became the coordinating body for Palestinian higher education, and it was the vehicle through which Arab funds were channeled.

Coordination was difficult, and frequently institutional aspirations took precedence over national planning. In 1979, the Council approved a proposal I presented for formula funding, whereby funding for Palestinian higher education institutions was based on indicators such as the number and rank of faculty and staff and the number of programs. The formula was adopted by the Jordanian-Palestinian Joint Committee, which had just been established to oversee the channeling of Arab funding for Palestine, and was used to fund Palestinian higher education for a decade.

Bold Moves

Securing Accreditation

In the midst of our efforts to develop Birzeit College into a university, the Israeli occupation authorities deported me to Lebanon on the evening of November 21, 1974. Four other Palestinians were deported with me that night. There were no charges. The only “explanation” given for this illegal action was a statement in the Israeli press that we threatened the security of Israel, a claim Israel routinely made when deporting Palestinians during those years. In fact, deportation was an easy way of getting rid of professional Palestinians against whom they had no charges that would stand up in court. Overnight, I had become a victim of this policy.

The Board of Trustees challenged my deportation and maintained my position as President of the University. I decided to set up an office in Amman, the closest geographical location to the West Bank and to Birzeit itself, where I would have a chance to meet with my colleagues from the University to follow up on official matters. I had two issues on my mind: one was to get accreditation for Birzeit, and the other was to get financial support. Both were complex and demanding objectives.

The effort to secure funding is the subject of a separate chapter. Here I focus on accreditation.

In the early seventies, we sought accreditation from the Government of Jordan, which was the legal custodian for the West Bank at that time. The application to the Government of Jordan was passed on to Jordan University to provide counsel on the issue. The University expressed two reservations, one political and one legal. Jordan University officials argued that an accredited university in the West Bank would provide graduates who were unable to find employment with a means to immigrate, which would work against the goal of encouraging the steadfastness of the people in Palestine. In addition, it observed, there were no laws to accredit nongovernmental universities in the region. (In fact, the establishment of private charitable or for-profit universities is only a recent phenomenon in the Arab world.)

The first graduation ceremony was planned for July 1976, but as of March of that year we had not yet secured the necessary accreditation. We decided to apply directly to the Association of Arab Universities, which was holding its annual meeting in Sulaimaniyya University in northern Iraq in April 1976; that was our only chance to secure the support we needed. Gabi Baramki joined me in Amman, and then we flew together to Baghdad and then drove the long and somewhat tedious stretch to Sulaimaniyya.

In Sulaimaniyya, we presented all the necessary documents and we spoke with many Arab university presidents. We spent a sleepless night awaiting the verdict in the meeting next day. Our request was approved with flying colors and I scribbled a quick thank you to the various presidents and left with Gabi immediately to Amman. News of the accreditation was flashed to Birzeit and the jubilation was as powerful as that which greeted the announcement of the development of Birzeit to a four-year institution. We were deeply satisfied knowing that the certificates that would be given to graduates in July 1976 would be issued by an accredited institution.

On July 11, 1976, the University celebrated its first graduation ceremony granting bachelor’s degrees, the first such graduation ceremony by a Palestinian institution. Gabi proudly announced the accreditation of the degrees. I also sent a short taped congratulatory speech to the students for the occasion. It was a challenge to do so because no tapes or letters were allowed across the bridge at that time, but I wanted to be part of this memorable day in the history of Birzeit. There was a big risk of having the tape confiscated, but it got through undetected. Luck was on our side that day.

The Intimate Relationship between Birzeit and Its Larger Context

Something surprising and unplanned happened within Palestinian society in the 1970s. People started nurturing and being nurtured by what was around and inside them; they started doing what they were convinced needed to be done. The lack of a legitimate authority gave people the freedom to do what they felt was needed, regardless of the price they might pay for doing it. One surprising aspect was the unplanned harmony in people’s activities. I experienced this often enough to believe that it reflects a natural ability within people and communities—an ability that I believe to be constantly suppressed by modern institutions. Specifically, between 1971 and 1978, we were left alone in the midst of a harsh reality with nothing other than what we had as persons, as friends, as a culture, and as communities. Teachers professed values and convictions that they believed in rather than being driven by gains or careers. It is in this sense that hope is connected to what is abundant in people, community, culture, and nature. We discovered the strength in us. Young people during the 1970s and the first intifada found their ways through the cracks within oppressive structures and surprised the world and each other with what they could do with what they had. Creativity in the 1970s as well as during the first intifada was collective creativity, not individual (although some acts took individual form). Similarly, leadership was “elusive” during these two periods. There were no charismatic leaders; leadership moved from one person or group to another according to the situation at a specific place and time. At the same time, there was a connection with the world at large; many people were in constant interaction with Birzeit and visited it. Birzeit was a mecca for academicians, writers, artists, activists, and students from all over the world. Birzeit’s intimate relationship with what was going on within the Palestinian context was a result of the absence of rigid structures and boundaries: no boundaries between the administration, teachers, and students; and no boundaries between the University and the surrounding community. There were no walls or gates within which students were caged and nonstudents kept out. University buildings were intermingled with people’s homes. The best way to describe its spirit is in terms of hospitality, a word not often used in connection with universities. Birzeit forms a Palestinian treasure. We would do well to dig into that treasure. In the 1970s, Birzeit was a small college, yet the world was inspired by it; its strength and worthiness sprang from within and from its relationship with the society around it. It sprang from a spirit of rebelliousness against any attempt to crush people.

Birzeit students in the 1970s were very active and alive: there was a lot of walking in surrounding areas and activities, such as singing, folk dancing, demonstrating, picking olives, clearing roads, and organizing book exhibits. Teachers and students interacted not during set office hours but rather throughout the day and in a variety of ways. Discussions about various topics were continuous. In a very true sense, Birzeit students were not only reading words but also reading life; their meanings sprang not only from books and dictionaries but also from experiences, contemplations, and discussions.

I would not describe what we did in the 1970s as optimistic but as actions that embodied hope. Optimism is related to some positive result in the future (an attribute of the mind), while hope is manifested in doing what one can do in the present (an attribute of living in harmony with life). Hope is a manifestation of the force of life. It is hard for a person who did not experience hope to really grasp what it means. It is an aspect of life that is difficult to express in words and to comprehend totally by the mind. Hope in the 1970s was manifested in thousands of spontaneous autonomous small acts.

The challenge facing Birzeit today is to regain the power of collective memory; it is a main weapon in people’s hands and every community has it. Palestinians don’t have mines of petroleum or gold, but we have tremendous treasures in terms of experiences, stories, history, and culture. I always stress that Palestine can serve as a magnifier through which we can see what is happening in the world at large. Some of the treasures which Birzeit had and which I mentioned earlier— how there wasn’t much teaching but tremendous learning, not much competition but inner callings, not much research but tremendous search for meaning—can be relevant for universities looking for a vision. The history of Birzeit is not only of closures and repression but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, and creativity.

All rights reserved. Published 2010

Birzeit University Publications

Birzeit University: The Story of a National University