A traveler I am, and a navigator, and every day I discover a new region within my soul.

Khalil Gibran

I felt rather strange the other day during a presentation titled "Creating Impact on International Youth in Palestine: Challenges and Opportunities." I was speaking at Birzeit University to a group of Palestinian Americans from Project Hope, a Palestinian youth initiative that seeks to connect young adults who live outside of Palestine with the city of Ramallah and to awaken, or cultivate, the spirit of volunteerism within the larger Palestinian community.[i] Repeatedly, I reminded myself that they are just like us, Palestinians too! But I felt insecure because for the first time in my life, the realization that separation from the homeland causes a feeling of being without place was striking me with full force – and I was wondering how this must affect their sense of identity. How can you find clarity when you are confused? The distinction, even if rough, is important: In that room, we were "neither completely one nor the other,"[ii] neither completely Palestinian nor American, neither fully at home nor away.

Let me try to be a little clearer: Does the memory of the loss of our land define us as Palestinians?[iii] How can Palestinians in the diaspora rediscover their lost identity when they are out of their place? As an educator who believes that true education should get us in touch with ourselves,[iv] I listen to the voices of our young Palestinian students, striving to elicit their innermost thoughts and encouraging them to reflect on the simple things that make a difference in their lives. I often ask myself, "How do these students feel, being in this room? Do they feel like me, a 'shape without form, a shade without colors, as wind in dry grass?'"[v]

I left the presentation burdened with the whisper that we are one but not the same. Some think, possibly rightfully so, that learning to live or leave involves a permanent transformation, especially when one is haunted by the feeling of al-ghurba (alienation). Defining our status as universal humans who lost their homeland to become the so-called Palestinian diaspora (الشتات الفلسطيني ) entails the understanding of hidden stories that are narrated by breathing stones. Our resurrected memories rise to make a decision, obtain a travel document, cross the bridge at the Jordanian border, and enter Palestine. Al-ghurba represents a radiant affirmation of the right to return, the right to what essentially has been lost!

In this sudden epiphany that stunned me in front of these young, dreamy Palestinian youth at Birzeit University, I understood that there is a new generation of Palestinians who are actively seeking meaning. They come to proclaim existence, which is essential to human experience. I also knew that as an educator I was making a serious decision: Generate opportunities for these young leaders who have come from all walks of life! By increasing mobility, by creating educational and cultural exchange programs and community voluntary service work, we can raise a generation of Palestinian youth who are in place despite geographical separation. "I had to make this journey to find my lost identity," Amal whispered in my ear.. "I changed from a teenage girl into an independent adult and learned to give myself the permission to live with a unique personality. Coming from abroad and having lived for four years in Palestine, I’ve learned that struggle has become part of our lives...

..But this struggle has never destroyed our will to live, love, learn, and laugh each day. To me, living in Palestine was an eye opener. I found myself.

Amal continued..

In Palestine, barriers to the integration of diaspora youth include not only linguistic and cultural challenges but also obstructions of the right to education that directly result from occupation policies. Education is a basic human right with the ultimate goal of teaching self-reliance. Here, education is a form of resistance. Palestinian universities face unique challenges when they attempt to participate in the global education market, as the lack of mobility caused by the occupation prevents Palestinian students from participating in international academic conferences and research. Therefore, the successful process of strategically integrating Palestinian youth from the diaspora into our educational institutions announces the beginning of a new era. It constitutes the commitment to create international awareness and promote global recognition of the right to return.

By allowing young students to visit and experience life in refugee camps, attend educational institutions, and participate in social service projects, Project Hope fulfills a national responsibility. As BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights points out, Palestinian students from the diaspora who return to their land of origin "affirm their Palestinian national identity not merely as a question of citizenship, travel document, or humanitarian privilege, but a much wider concept concerning the key principles of liberation, freedom, and democracy. Sixty-eight years after the Nakba, alienation and displacement unite all Palestinians at a regional, and possibly global, level."[vi] The survey, focusing on identity and social ties, clearly indicates that the third and fourth generation of Palestinian refugees did not "forget" their attachment to Palestine.

Like many other Palestinians, al-ghurba has haunted me for years, even though I have been physically here, living in Palestine. This intensely painful feeling can be countered only by the stories that we as Palestinians continuously re-collect in order to create a common memory, a collective identity to resist the occupation. Therefore, I attest to the power of my grandparents' voices and legacy. And I furthermore attest to the voice of a vulnerable, yet powerful boy who grew up in a complicated world: Edward Said. One of the most important intellectuals of our time, Said crafted an extraordinary story of exile and a celebration of our irrecoverable past in his memoir Out of Place. I have never felt closer to Said than recently. His sincere representation of the experience of an American immigrant reflects and incites a dialogue between the self and the community. How was he able to regain this voice from within?

I will always remember my mother’s voice; she is here with me all the time. Similarly, despite their physical absence from the land of olives, Palestinians in the diaspora compose a symphony that is in tune with other Palestinians. Our grandparents left but kept their stories with them for us to collect. To me, Al-Nakba day is not only about mourning, I also envision hopeful children running after their Palestinian flags in the streets of both Ramallah and Chicago. Indeed, the memory of the Nakba’s is revived in the stories narrated by our grandparents. But the power of these testimonies marches in time to restore our homeland – which to many of them was little more than the memory of a place.

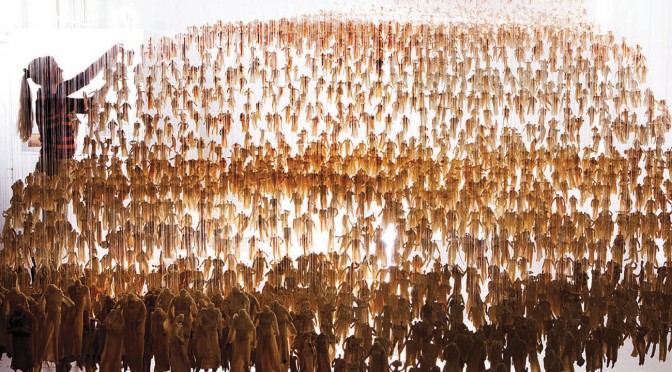

"Return of the Soul" by Jane Fere, a Scottish based painter, theatre designer and now multimedia artist who revisits in this project the Nakbah, the catastrophe that befell the Palestinian people in 1948 when the newly UN-sanctioned nation of Israel expropriated ‘lebensraum’ (living room) through violent ethnic cleansing.'Part of the Edinburgh Art Festival'

BLURB: "Time heals," Sireen told me. "I was raised in the US and came to live in Palestine at the age of sixteen. Now, I am getting my BA in English language and literature from Birzeit University, with my husband and two daughters by my side. I admit that coming here was one of the best decisions I made in my life. The people who have lived under occupation have more life in them than I had, and they have given life back to me!"

Witnessing how Palestinian youth learn how to care and seeing them grow in knowledge with great wit and passion teaches and reinforces the notion that as human beings, indeed we are capable of love, and when we love we are better. Halima considered thoughtfully, "Walking through life without a true identity is not a life worth living. I was born in the States and grew up in Dubai. Then, I moved to Palestine, my country, to attend university. Living outside of Palestine, I was always considered Palestinian and I held great pride in that. I never once felt ashamed of who I am and where I come from. But coming back to Palestine was difficult because the people around me have and will always see me as the ajnabeyya, foreigner. That is something I apparently cannot change. I came here to be in my home country and live with my people. But how can I do that when the single characteristic that causes me the most pride is the one thing stolen from me: my identity of being a Palestinian? Could it be true that I am not Palestinian, as some say? Or is it of no importance where I've lived or will live? Will my Palestinian identity always be present? I feel Palestinian and I am from Palestine, so the only answer to the question of who I am must be..

I am, and will be forever Palestinian!

Her words have touched my heart. I know now that creating one's profile as refugees must be an endless battle. Acknowledging that these young Palestinians are nothing but in place, I wonder what Edward Said's assessment of all this would be. In his article "Unifying Diaspora: Palestinian Youth Reassert Their National Identity," Amjad Alqasis demonstrates that according to the recent BADIL survey, Palestinian teens across the world have strong ties to their national identity, even though most of them have never (been able to) set foot into their homeland. The impact that Palestinian youth who return to their homeland leave on Palestine and on its people is huge and goes beyond solidarity action. My personal experience of interacting regularly with these young diaspora Palestinians who come to Birzeit to learn their Arabic mother language and live their culture lets me consider their engagement as part of our March of Return. We declare in successive waves our mobility and our intention to revive a valued right: We Will Return and We Are Here.

I am definitely not the same person I used to be. The voices of my students and many more remind of what matters. It is the March of Return. Far away from words like diaspora and al-gurba, words that are intensely resonant in the Palestinian lexicon, I feel now less alone and more loved.

[i] The American Federation of Ramallah, Palestine’s (AFRP's) Project Hope program was established in 1997 by then AFRP President Salem Mufarreh as a means of furthering the federation’s four founding principles of charity, culture, education, and society, principles that have guided the AFRP’s coalition of clubs since 1958.

[ii] Edward Said, Out of Place: A memoir, Vintage, 2000.

[iii] Elia Zureik in the book review of Helena Lindholm Schultz, Palestinians in the Diaspora: Formation of Identities and Politics of Homeland, and Maya Rosenfeld, Confronting the Occupation: Work, Education, and Political Activism of Palestinian Families in a Refugee Camp, published in the American Journal of Sociology Vol. 111, No. 3, 2005.

[iv] Sydney Harris, "What True education Should Do", in M.C. Feldstadt, ed., The thoughtful Reader, Harcourt, 1994, available at https://emu.edu/writing-program/faculty-services/articles-handouts-exerc....

[v] T.S. Elliott, Mistah Kurtz-he dead, epigraph to The Hollow Men (poem), available at http://www.shmoop.com/hollow-men/poem-text.html.

[vi] One People United: A Deterritorialized Palestinian Identity, Survey of Palestinian Youth on Identity and Social Ties, 2012, BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, available at http://www.badil.org/phocadownloadpap/Badil_docs/Working_Papers/WP-E-14.pdf.

This Article was originaly published in This Week in Palestine, view full article here.