2018 study points to decreases in natural areas, increased building concentration as results of Israeli policies

In a study titled “Landscape change in Ramallah-Palestine (1994–2014),” Samar Nazer, a professor of architectural engineering at Birzeit University; Sara Khasib, an instructor in the department; and Rana Abughannam, who previously taught at the university and is now a PhD student at Carleton University’s School of Architecture and Urbanism, investigate and explain landscape changes in the city of Ramallah since the signing of the Oslo Accords, painting a picture of explosive urban growth exacerbated by restrictive Israeli policies and practices.

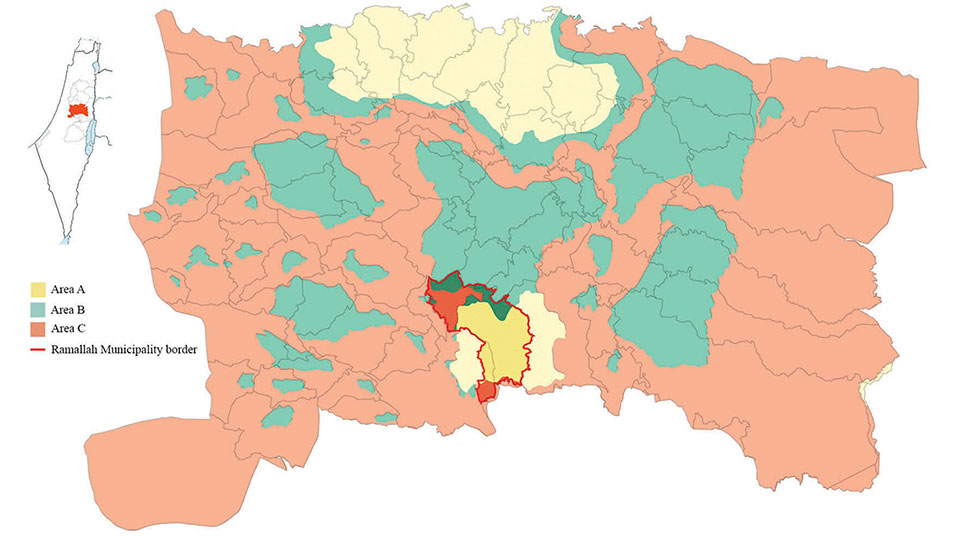

The Oslo Accords, comprising two agreements that were signed in 1993 and 1995, created the Palestinian National Authority (PA) and reshaped the Israeli-occupied West Bank, dividing it into three distinct areas: Area A (under the civil and security control of the Palestinian Authority), Area B (under Palestinian civil administration but Israeli security control), and Area C (under Israeli administrative and security control).

This redrawing of the borders combined with the limited authority of the PA, has resulted in a series of landscape changes across the West Bank, fueled by unplanned population growth and urbanization, resource scarcity, and, above all, aggressive and limiting Israeli policies.

Nowhere in the West Bank is the effect of these factors clearer than in Ramallah, the current seat of the Palestinian government that has witnessed the return of Palestinians driven out in the 1948 Nakba and the urban migration of Palestinians who have come from towns and villages throughout the West Bank in search of employment, attracted also by the better living conditions available in this city.

The study focuses on human-caused landscape changes and investigates the magnitude, frequency, impact, and patterns of physical alterations that have taken place over the past 20 years in Ramallah. It is part of a larger research project, undertaken by the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate, which investigates the ongoing landscape changes and explores the reasons behind these developments in the cities of Ramallah, Al-Bireh, and Betunia and their surrounding villages and areas.

The authors scanned aerial photographs, taken of Ramallah between 1994 and 2014, to trace differences in land usage and patterns of landscape change, employing GIS mapping and statistical analysis and adapting the CORINE Classification System to create a land-usage database for the classification of their information.

In the cited study, the authors focused on four main classes of land use: areas where permanent agricultural trees are cultivated, areas with scrubs, built-up areas, and paved roads. They found that, from the total surveyed area, the areas where agricultural trees are cultivated have decreased from 33.1 percent in 1994 to 25.6 percent in 2014; the scrub areas have shrunk from 46.4 percent in 1994 to 41.9 percent in 2014; the built-up areas have increased from 11.4 percent in 1994 to 20.7 percent in 2014; and the areas with paved roads have increased from 4.3 percent in 1994 to 6.7 percent in 2014.

Other landscape changes noted by the authors are an increase in arable land by 18.7 percent (of the total surveyed area, from 2.5 percent in 1994 to 3 percent in 2014), a decrease in the open areas in which trees are cultivated (from 1.3 percent in 1994 to 1.2 percent in 2014), and a decrease in coniferous forest areas (from 0.3 percent in 1994 to 0.2 percent in 2014).

These changes, the authors argue, highlight “new urban patterns in Ramallah, which in general are becoming more fragmented and discontinuous,” noting that, taken as a whole, the changes point to a disconcerting development that “poses the threat of additional losses of natural resources and biodiversity due to further urbanization.”

The authors attribute these changes and alarming trends to a population increase in Ramallah - due to socio-political factors - and, more importantly, to the increasingly restrictive Israeli policies, causing the Ramallah municipality to grant building permits on natural areas to accommodate population growth. The authors also point to the Israeli policies of settlement building and land fragmentation (and the associated movement restrictions) as reasons for the concentration of build-up areas in the city because they decrease the land available for Palestinian urban expansion and cause travel delays, enticing Palestinian urban migration.